Flying A Drone With Camera Gear

Since the dawn of portable and affordable drones, U.S. based videographers have been caught in a difficult position. It turns out, flying a drone with camera gear means something completely different to the FAA than flying a remote control helicopter without a camera.

That means even a tiny consumer drone like the DJI Spark, which weighs 10 ounces, is considered a potential threat to public safety when used by a working video producer.

It's not that the camera adds a privacy concern - it's that a drone with a camera becomes a highly profitable commercial activity, and that has federal regulators very interested.

You can fly drones for a hobby - like millions of people do - or you can fly drones professionally in countries where it’s allowed, or you can sit back and wait for the FAA to come up with reasonable regulations that would allow for legal, commercial use of drones for filmmaking purposes in the U.S.

Or you could just take the risk, like many have done, and use a drone in your small time videos and hope and assume nothing will happen. After all, everyone else is doing it, right?

It's commonplace to spot drones everywhere these days. We saw this one at SXSW in Austin.

And then you hear about someone very similar to you, who flew a regular DJI Phantom for a small job, and something happened that triggered an FAA investigation and the videographer is now liable for thousands of dollars in fines.

Uh oh, you think. Well, I’m not charging for my drone work, you say to yourself. It’s just a bonus to my bread and butter video work. But then you hear that if you’re a professional videographer and you publish any drone videos whatsoever, it is deemed as promotional for your business and thus commercial in nature.

So then you crunch the numbers. How much could I get sued for? $10,000? Maybe it’ll get settled at $2,000 like the few cases have? Maybe it’s still worth the risk, to continue to offer drone video as part of my services - perhaps under the radar - and accept my fate when I receive that letter from the FAA?

FAA 333 Exemption for flying a drone with camera gear

After a few years of deliberation, the FAA finally opens up the 333 Exemption, which is a relief for videographers flying a drone with cameras. Now you could unpack your little DJI Phantom, get it up in the air, and take all the video you wanted with full support of the law.

You pour yourself a glass of Chablis to celebrate, go to sleep, and wake up to get started on your paperwork.

And then you realize the 333 Exemption is no easy hurdle. Most likely you’ll have to hire a lawyer, perhaps one of the few lawyers who have set up a business to exclusively file 333 paperwork for video producers. There are 50,000 applications ahead of you, but if the paperwork is drawn up correctly, you assume, in 3-4 months you’ll be in business. You calculate maybe $1,000-3,000 in expenses, and decide it’s still worth it.

But then you read the fine print. As the owner of the 333 Exemption, you don’t have to have a pilot’s license yourself, but someone flying under your exemption does. And a sport’s pilot license can take months of your life to acquire, not to mention the additional thousands of dollars. Bah humbug.

So you go back to just not worrying about it, assuming that you’re one of a million other videographers who use a drone in their videos, and hope nothing will come of it. After all, you fly well under 400ft, you stay away from crowds, you don’t fly anywhere near an airport, and for the most part, you’re just getting 4-5 second shots to sprinkle into your video about a nonprofit or small business here and there. Nothing serious.

FAA Complaints for videographers flying a drone

And then you get an email or a phone call from someone in your area who went through the trouble of getting a 333 Exemption. They’ve spent a lot of time and money to become certified, legal commercial drone operators, and they have seen the videos you have made and know for certain you’re not 333 certified. So they give you two options: hire them for all your drone needs, or they’ll rat you out to the FAA.

You kindly tell them thanks, but you can’t afford them. They hang up, saying the FAA will be in touch. Your blood begins to boil a little. Would a fellow video producer really go to the trouble of making a formal complaint to the FAA about your measly little drone clips you made for a nonprofit mission video?

Two weeks later you get a phone call from the FAA.

They ask you about a couple drone videos you shot two years ago. You remain calm, and tell them it was an unpaid gig. But as you already know, whether you got paid is irrelevant if you're a photographer or videographer. If you're flying a drone with camera gear, even if it's on personal time, it's still considered promotional for your videography business.

They ask if you know the rules. You tell them yes, and you try to diligently abide by them. They tell you they’re sending a letter informing you of the rules. And at this time, that's the extent of their case with you. They also tell you that the FAA will very soon be coming out with new regulations that will allow commercial drone operation, without a 333 Exemption, without a pilot’s license.

You tell them that sounds really great, and you promise them you won’t fly your drone until the regulations are announced. Meanwhile, your heart is racing. In the back of your mind, you’re thinking, "God, I am never flying a drone ever again. It’s just not worth all this."

Drone Videographers becoming drone police

Everything above actually happened to us, and we’ve heard the same stories from others around the country.

And this whole time we’re thinking, you know, the FAA people are actually really nice and professional, and they probably don’t enjoy having to respond to petty complaints about small time drone use.

And worst of all, FAA officers most certainly don't appreciate Section 333 operators using the FAA as a method of threatening and extorting other drone operators into hiring them.

It's a shame the drone police has taken the joy out of posting beautiful drone pics and videos.

So what it comes down to is, other people in the drone filmmaking community are going out of their way to create problems for uncertified drone operators. They’re doing it as a way to position themselves as the preferred hires for local drone work, which might make sense for them but is a preposterous way of promoting their business. In the meantime they’re out there policing any and every small time videographer who posts any drone shot whatsoever.

The “drone police” is what makes sharing aerial videos incredibly negative these days. And it also makes writing about flying drones totally unpleasant. No matter what you post, the drone police - other, more informed drone operators - will attack you for saying or doing something that’s against the rules.

And while we encourage educating other drone operators anytime their footage is clearly in violation of FAA regulations (like the festival photo from the top of this article), you can't post hardly any drone pics or video without having to defend yourself from the drone police questioning whether your footage abides by the rules.

All of it makes flying a drone with camera gear a huge headache and ultimately much more frustrating than it should be. After all, shouldn't flying a quadcopter be fun? Why did adding a camera to a long-standing RC hobby suddenly turn the community into a battleground?

FAA Part 107 for flying a drone with cameras

So with all that said, we were elated when the [FAA released the new Part 107](faa part 107 waiver) regulations and certification process to fly drones commercially in the U.S. We immediately began the process of studying for the test, and then passed the test a couple weeks later.

We got the Part 107 certification not to go out there and make a business out of flying a drone with cameras - we rarely fly drones for any video project these days - but we did it so we can finally learn what the actual rules are and be comfortable in knowing that we’re flying safely and legally.

And we also got the Part 107 certification so we can finally post videos and write about drones, without dreading that the drone police will call us out for doing it wrong.

If you identify with anything we’ve said so far, then kudos to you, and we think you should also get the Part 107 certification. And to help you do that, we’ve compiled some of the lessons learned, study guides that were helpful to us, as well as overall tips for passing the test.

How to Study for the Part 107 Exam

In the process of studying for the Part 107 exam, you actually learn a lot about what it takes to fly remote drones safely. Sure, you can find a flying school out there that will help you learn to fly UAVs, but for the most part drones like the DJI Mavic Pro are incredibly simple to fly.

So it’s not the operation that is challenging - it’s the safety measures, aeronautical rules and regulations, and overall seriousness of flying drones that are the important parts of drone pilot training. And you learn those components while studying for the Part 107 exam. In a sense, the Part 107 exam is actually the best drone pilot training out there.

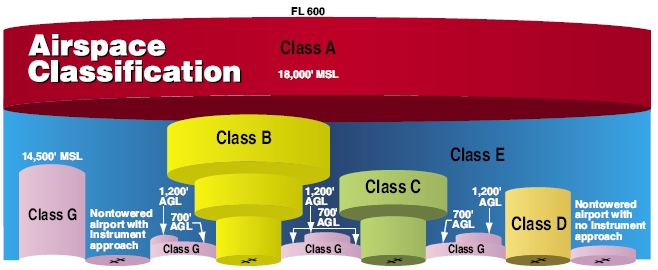

Instead of teaching you about how to operate your drone, these are some of the things the Part 107 exam addresses:

- Where and when can I fly?

- What if I want to fly within 5 miles of an airport (i.e. any major urban center)?

- How do I read weather reports to determine when it’s safe to fly?

- What kinds of personal emotions or traits should I be aware of that may inhibit my ability to fly safely?

- What should I do if I spot an airplane or helicopter near my drone?

- How do I ensure drone maintenance procedures before lift off?

- If I crash my drone, when and how do I report it to the FAA?

- If there are multiple people assisting with the flight, who is ultimately responsible for the drone flight?

- Can I fly my drone while riding inside of a vehicle, or boat, or other moving platform?

- How is flying a drone with camera gear different from flying an RC copter?

- How do I make sure I’m abiding by the full extent of the law anytime I’m flying my drone for commercial purposes?

FAA Test Prep

To get started in preparing for the Part 107 regulations, you could read the assortment of PDFs and advisory documents and press releases that spell out every aspect of the regulations. But if you’ve ever looked at the FAA’s website, the dozens of webpages and PDFs are convoluted and difficult to understand.

Luckily, there are a few websites that have interpreted the Part 107 FAA test and have provided the appropriate study guides and FAA test questions that help you study for the exam.

In our opinion, the most comprehensive site is http://www.sarahnilsson.org/drone/drone-pilot-ground-school/uag-test-prep-1-intro-regs/.

This site combines material from several FAA guides into one long read. You get not only the sUAS Part 107 test prep, but also guidelines and FAA test questions from the Part 61 Remote Pilot exam.

It will take you a week to read, comprehend, and memorize this all encompassing guide, but in the end you’ll feel over prepared, which is a good thing.

FAA Part 107 Practice Test

Once you’ve gone through all the material on this site, and you feel like you’ve aced the practice test questions, head on over to https://3dr.com/faa/drone-practice-tests/

3D Robotics has discontinued their Solo drones, but it looks like their practice tests are here to stay. They’ve compiled many different test questions that will help prepare you for differnet wordings, charts, and weather-related questions that you will come across on the Part 107 FAA written exam.

And finally, we recommend http://jrupprechtlaw.com/part-107-knowledge-test

This site publishes the standard FAA test prep questions, but it goes a little further in explaining the rationale for the questions and answers. As you can expect, some of the FAA questions are tricky and maybe even a little bogus, so these down-to-earth explanations help you realize that you’re not insane and that some of the questions are meant to be difficult.

FAA written test centers

Once you’ve spent the time studying the regulations and you feel like you can ace the FAA test questions, it’s time to put your training to the test and schedule an exam at an official FAA written test center.

Each attempt at the test costs $150, and if you fail there’s a mandatory waiting period between your next test, so it behooves you to pass the first time.

You’re allotted 2 hours to take the test, but in our experience we finished at a little over an hour. At the end of the exam, you’re asked if you want a proctor to review your incorrect answers, but they ask you this before you know if you have any incorrect responses.

In our case, we decided to peel the bandaid and just face the results, without explanations for what we got wrong. And after studying nonstop for a week, and feeling like we had everything down, we still missed 8 questions.

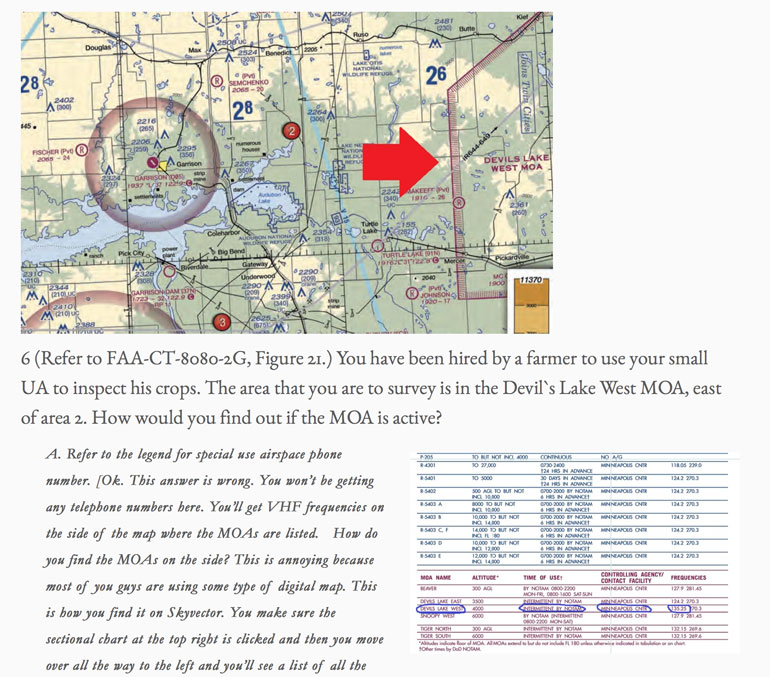

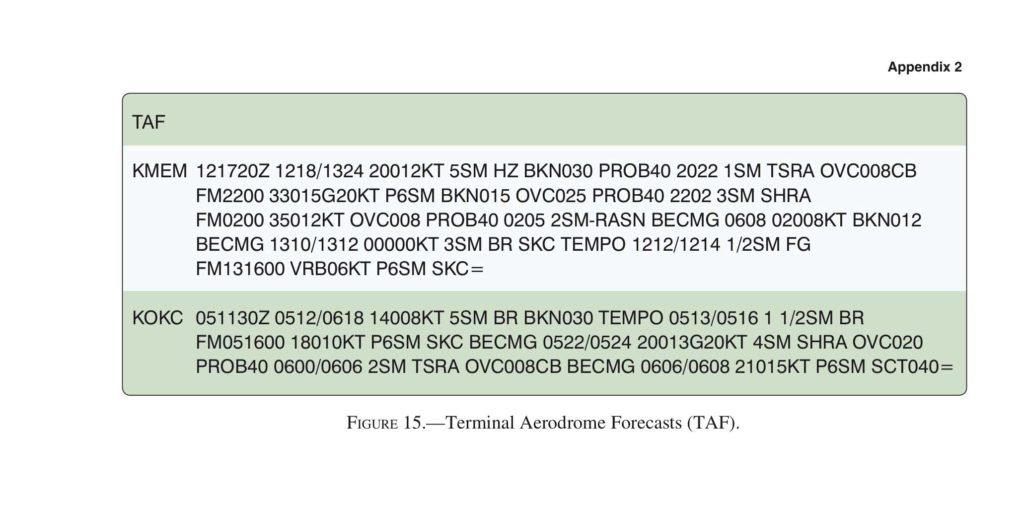

You should be able to read these TAF reports to pass the test.

You’re allowed to miss 18 of the 60 questions, so we were well within the passing range. But still, let this be a warning to you, do not take this test until you feel 100% certain you can pass it. It’s a difficult test. And this is coming from us who have always been great at taking tests.

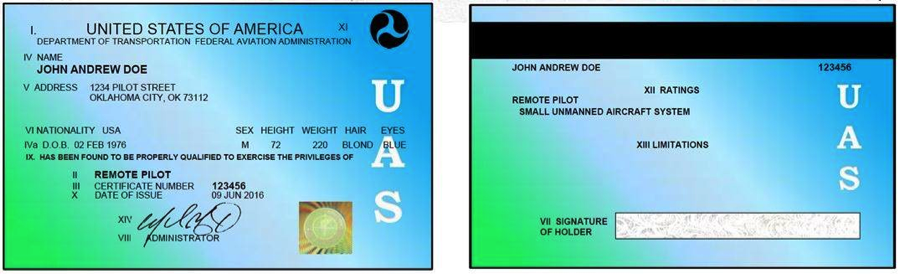

FAA Remote Pilot Certificate

After you leave the test center, you have to wait a few days for your test results to reach FAA, before you go and sign up for an online account, fill out all the (online) paperwork, and wait for TSA clearance before your official certificate arrives in the mail.

Ours took nearly 2 months to arrive. In the meantime, you can print out a Temporary Airman Certificate, which allows you to go out and fly legally until your official certificate arrives.

You also need to register your drones, each of them if you have multiples, and pay a $5 fee per unit. This is a different registration than the one you have to do as a hobby pilot, which gives you one FAA number to stick on all of your drones. The commercial registration provides you a different number for each UAS you own.

The one issue we ran into is you have to provide the serial number of the drone to register it. If you still have the box from your purchase, you’re golden. But in our case, we have a DJI Phantom 2 from a few years ago, the box long discarded, and our FPV system has been glued onto the bottom of the drone, covering the serial number.

We peeled back the FPV part slowly and found that the serial number had completely transferred to the bottom of the FPV transmitter, and only part of the serial number was still visible. After a long search online to find out what a typical Phantom 2 serial number looks like, we finally found a website that listed one Phantom 2 serial, which told us how many digits we were looking for.

We ended up taking a photo of the faded serial number, imported it into Photoshop, and then played with the contrast until we could finally make out what the serial number was. Phew - all that for a drone that’s not even 4 years old, but in the drone world is ancient history.

Where Flying a Drone with Cameras Is Allowed

Now that you have your certification, the biggest question is where can you fly your drone? This is an incredibly complicated question, and even the Part 107 test and training won’t give you a simple answer. Because even if you’re clear to fly in an area one day, there could be a temporary order to cease all aircraft in an area for a limited timeframe, like if there’s an emergency or fire, or if the POTUS is flying nearby.

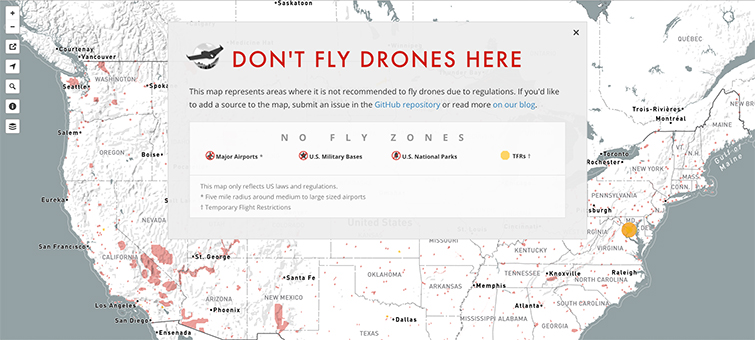

On most days, however, you have from sunrise to sunset to fly a drone, and it’s up to you to find out if you’re flying in an area that is restricted. You can use your drone pilot training you’ve gleaned during the Part 107 study and look at official charts to see if there’s any military restrictions or airports in the vicinity, or you can use the power of the internet.

FAA’s best attempt at an app, the B4UFLY app for smartphones, is good but it’s limited. The objective is for you to input your desired flying area, and the app will tell you if there’s a no fly zone nearby. In addition, you are instructed to input your flight plan, such as the maximum altitude of your flight, and it will submit the information on your behalf. Where does that info go? And does this procedure count as getting clearance to fly? All consensus points to no. So in reality, the B4UFLY app shouldn't be your only source of information.

There’s also the Know Before You Fly web app - http://knowbeforeyoufly.org/air-space-map/ - that takes FAA info and presents it in a clear map. But again, the information here displays a ton of road blocks that may not actually restrict your flights, such as small independent airports and landing strips that are defunct and not currently restricted fly areas for drones.

The very best resource we’ve found is this U.S. Air Space Map that you can download for Google Earth. http://www.soaringdata.info/aviation/airspaceTab.html

It gives you an up-to-date visual map of all the airports and other restricted airspaces in the area where you plan to fly.

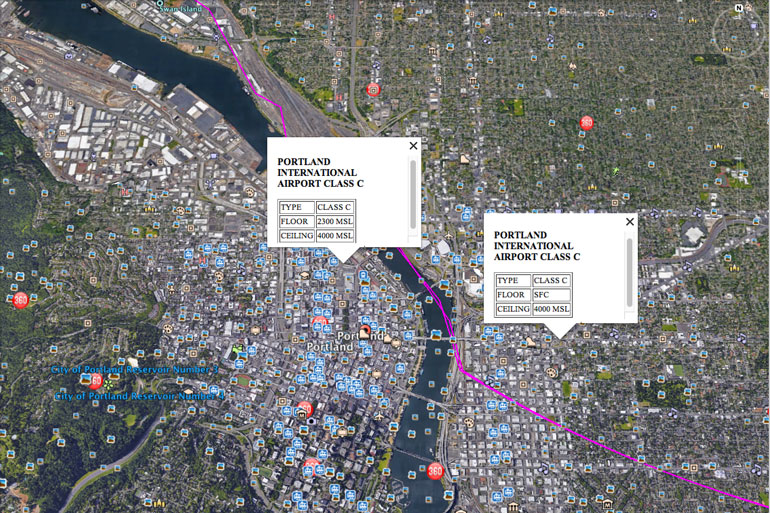

You can see in the above screengrab that if you plan to fly in Portland, Oregon, you can click on any point and find out what the floor and ceiling is for the restricted airspace. In this case, west of the Willamette River the floor is comfortably above your maximum 400 feet drone altitude, so you can fly there (as long as you abide by other rules like not flying over people). East of the river, the floor is surface level, so you can't fly there without acquiring permission.

Flying A Drone with Camera Gear near an airport

Once you know where you plan to fly, and you’ve checked the charts or maps, what happens if your flight falls under a restricted airspace such as a major airport? Well, that is the biggest hurdle by far.

The goal is to fly your drone within complete respect of the rules and regulations of FAA and the air traffic control for your nearest airport. But how to do that is still a huge challenge.

For hobbyists, you’re instructed to notify the ATC (air traffic control) of your plans to fly within 5 miles of a major airport. But the question is, are air traffic controllers aware of how to handle these calls? It varies significantly from airport to airport.

Here’s a phone call a Youtuber made to a local airport in Florida. After numerous phone pass offs, he finally reached an ATC officer who politely said thank you for the notification, and the drone operator was on his way.

For Part 107 certificate holders, however, calling air traffic control is not official protocol. Instead, you’re instructed to write a letter to the FAA seeking permission to fly within the restricted airport airspace, and they recommend at least 90 days in advance of your flight.

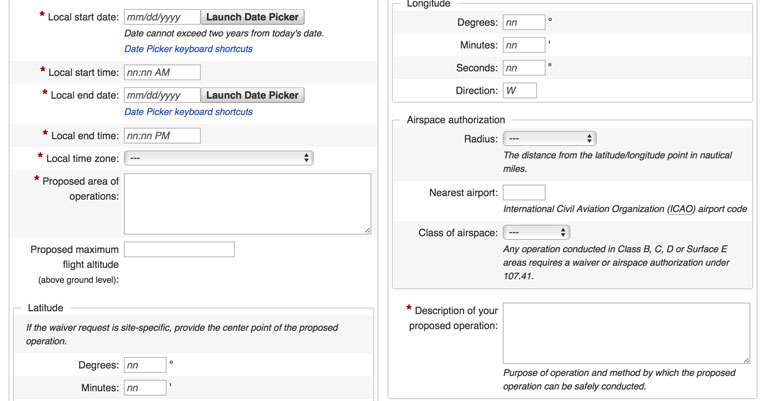

You have to provide details of the specific day and time you’re intending to fly, as well as the route and maximum altitude of the drone. And then presumably the FAA will coordinate that information with the airport ATC before giving you clearance to fly.

90 days in advance of flight? Who knows when and where they’re going to fly that far in advance? What if the weather changes and alters your plans at the last minute?

Our explanation is this: the FAA assumes that Part 107 certificate holders will fly their drones for more than just videography purposes. There are major Hollywood productions that utilize drones, and their schedules are set months in advance. But more than that, the FAA presumes that there are drone operators who may want to operate commercial businesses that inspect towers, possibly towers near or directly on airport premises, so a 90-day window is not out of the question for these businesses.

But for most of us flying drones to add spice to our small-time videography projects, often we don’t know if we’re hired for a project until a week or a few days before we show up. And because of that, our simple philosophy is to avoid shooting within 5 miles of airports altogether.

Now, if you live in a major urban area, that could mean you simply can’t fly your drone for commercial purposes in any part of town. The last place we lived in, Anchorage, Alaska, has 4 airports that cover the entire town with airspace restriction.

Are we going to seek clearance from 4 air traffic control towers 90 days in advance of our project, where we plan to fly 75 feet in the air to showcase a small business’s building space? No, we’re simply going to avoid offering drone shots for that space altogether.

But if you live in one of these major metropolitan areas and the majority of your video business takes place within an airport zone, perhaps you might tackle the waiver process, or you might decide to once again ignore the rules and fly under the radar.

So in the end, the drone pilot training you receive - by studying for and taking the Part 107 exam - gets you back to where we all started. We all want to fly within full support of the FAA and its regulations, which are both freeing and yet suppresive at the same time.

So maybe you think that, well, everyone else is doing it, so why shouldn’t I? Maybe you think the potential risk of a fine is still worth the added benefit to your video business? Or maybe like us, you realize the joy of flying a drone with camera equipment in areas where you’re legally allowed to do so is enough justification to get a Part 107 certification, so you can stop worrying about the drone police coming after you.

And you leave the complicated world of seeking airspace clearance to those who make a living from flying drones, rather than those of us who just want to add a quick aerial clip to our video about a local nonprofit.

Conclusion

There’s something about drones that bring about the best responses from clients and video audiences, but the worst from the general public. It’s kind of like shooting video in public used to be a terrifying dance between capturing footage that makes your video shine, but also dealing with an assortment of permits and begrudged people who did not want to appear on camera.

It was almost as if all the warnings and public postings made people think there was something sketchy about appearing on camera, and so they assumed it was an overall negative experience even before knowing what the shoot was or for what purpose.

It’s the same thing when you're flying a drone with camera gear these days. Clients love drone footage, the audience is continually inspired by amazing drone shots, and yet media reporting is leading the general public to assume something is awry with drones. Maybe it’s the privacy concerns, or the potential for accidents, but all we know is when we fly our drones we are almost always confronted by a passerby who are upset about the whole thing.

And then once you post the footage, there are people - many of whom are videographers or dedicated drone operators themselves - who feel compelled to police the drone footage and point out every potential rule or regulation that you may be breaking. This is under the auspices of wanting everyone to fly safely so that one person doesn’t “ruin it for the rest of us,” but we also know that many of the drone police are local competitors who aim to bring non-compliers down in order to elevate themselves as the best hire for drone work.

It’s all quite depressing, and it’s why talking or writing about drones is a challenge, because no matter what you say, someone has a rebuttal to your assumed understanding of the law and regulations. And it’s not always helpful advice.

So the best thing you can do is to take the drone training that the FAA provides with the Part 107 certification, learn all the rules and regulations, go out and fly within the areas that are deemed safe, and then leave the controversial stuff to others. In the end, you’ll have to take the FAA Part 107 test again in two years, and by then the world of flying drones might transform into something entirely different.

In the meantime, go enjoy the world of drones and all they have to offer. We highly recommend the DJI Mavic Pro for all your drone videography needs, and the PolarPro Cinema Shutter ND filters as our favorite essential drone accessory - check out our Mavic Pro ND Filter review.

Happy flying!